A few weeks ago a controversial picture by Artist Daniel Winship appeared online. It was controversial because it portrayed a child receiving a cochlear implant while wide-awake and screaming as a doctor drilled directly into his head.

The picture has been shared over 600 times on Facebook as debate raged in the comments. Our own contributor, Calum Fox, wrote about the picture here two weeks ago and today we can bring you an interview with the artist by US deaf journalist, Tara Schupner Congdon, who blogs at Jayhawkeditor.com. In the interview, Daniel Winship explains why he created something so controversial.

…

An illustration of a child undergoing cochlear implant surgery, created by Daniel Winship and posted on his Facebook page (warning: explicit) and shared more than 600 times, has generated heated, acrimonious debate among members of the deaf community, including those with implants, and hearing people connected to the community – particularly hearing parents of deaf children with implants. It’s also raised challenging questions about expression through art, how individuals interpret and react to it and each other, what qualifies as propaganda and bullying, and censorship.

Commenters have used a range of words to describe the illustration, including powerful, evocative, propaganda, utter nonsense, crap, an evil depiction, sensationalistic, and patently false. Winship himself has been accused of brainwashing, labeled a sick person, and called a ****, “closed-minded arrogant t***,” and wacko on the same level as members of the Westboro Baptist Church. Others have made assumptions, including that Winship must be an ex-implantee, that he doesn’t have children – much less any with “a birth defect” – and that his illustration reflects the opinion of the entire deaf community.

After reading the 200+ comments posted on his image, I decided to seek out the man behind the art and find out who he is and why he created the illustration when and how he did. I spoke with Winship and his wife, Darleen Hutchins, via phone. The following is translated from American Sign Language, and I’ve written a commentary below the interview.

Daniel Winship on his art and life: An interview

Tara: So, Daniel, what inspired you to create this illustration? Any particular event?

Daniel: I had been talking with friends about cochlear implants, and these conversations just stuck in my mind. Then someone did a vlog about implants and oppression of the deaf. At the same time, over the past month I’ve focused on making art about deafness. I usually make art for the hearing and don’t share my deaf-related art, just started doing that recently. So one day I just sat down and started drawing this to express myself, looked at what I’d drawn, and just added to it and expanded it. I was thinking, how would I feel if I was that child? And I was exploring the idea of a deaf soul. Children are a symbol of innocence, of an innocent deaf soul.

I like to challenge myself with different ideas, in art, and themes about deafness. I didn’t feel any particular intense emotions when I started this. I was just thinking outside the box, doing a study of sorts.

Tara: So, what was your purpose behind posting this to Facebook?

Daniel: I really just posted it to see what people thought and observe reactions. The reaction I got was very unexpected.

Darleen: We had been discussing art, deaf art, the impact of art on the community, parents, et cetera. It took a LOT of guts for him to post that picture. That’s not something he does. His art tends to be dark, so he doesn’t share it that often. It was just his way of saying, “I am here.”

Tara: Where did you originally post your illustration to? Only a few places, or everywhere?

Daniel: Only to my Facebook page, Deafhood Discussions and De’VIA Art. It was very limited, but people just shared it and it exploded from there.

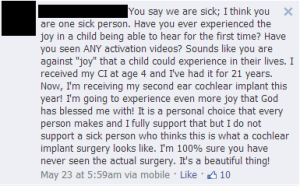

“I do not support a sick person who thinks this is what a cochlear implant surgery looks like. I’m 100% sure you have never seen the actual surgery. It’s a beautiful thing!”

Tara: Were you trying to depict what the surgery actually looks like?

Daniel: No, I wasn’t trying to do that. Just my own envisionment of it. I’ve had surgeries before, and I have some common sense of what a surgery looks like. I wasn’t trying to represent the actuality, just elaborate the idea with my own modifications.

Tara: What was your goal with it? Were you hoping to change people’s minds about the surgery or cochlear implants?

Daniel: Oh, definitely not. No. It absolutely was not my goal to change people’s minds. I only created it for myself and then decided to share it, to share my own thoughts.

Tara: Now, I want to ask … what type of background do you have? What was your experience growing up?

Daniel: I was adopted by a hearing couple. I started out with hearing aids and Total Communication, isolated in the mainstream. Then my parents found out about the deaf school (in Maine) and moved me there when I was about 6 or 7 years old, in 1983. I did a half day there for full access to language and social access, and half day in the mainstream for math, art, gym and to have better education. I still use my hearing aids sometimes to help my hearing in certain situations like movies and music.

Tara: Darleen, what about you?

“How dare you judge someone else, in a situation you know nothing about? If your child were born with a birth defect – which is what deafness is – I guarantee you that you’d explore every option to give them the most whole and complete life possible. That, my dear, is what “love” truly is.”

Darleen: I grew up oral. Learned sign at 14, when I transferred to the deaf school in Maine. That was just after Daniel had graduated. Then I went to a very small college.

We have a deaf daughter, you know, and a hearing son.

Tara: Did you two discuss a cochlear implant for your daughter? Did you think about implanting her?

Daniel: No, no. She lost her hearing later, but we decided not to give her one. We felt we didn’t want to get sucked into that cycle, what if her implant broke or didn’t work? We’d have to keep going back and going back and going back to get it tweaked and fixed. We did not want her dependent on that technology. She is just fine as she is.

Tara: Daniel, someone commented on your illustration that you have friends with CIs, some who don’t use them anymore and some who still use them?

Daniel: Yes. Quite a few.

Darleen: You know, one of the first children to get a cochlear implant was from Maine. He doesn’t use it anymore. He actually said, “I’m not using this stupid thing anymore.” And one of my own friends was tricked into getting a CI at 21. Her parents never told her why they were taking her to the hospital, and she woke up with an implant. I was the first deaf person she met in college. She is very angry about the implant now. She has called it her “ball and chain.”

Tara: What about people who are “successful” implantees?

Daniel: I don’t meet a lot of people like that. Just mostly people who don’t use their implants anymore. I met a man whose mother tried to bribe him to get one. She told him she would buy him a car if he would get an implant. So, things like that. Before, I didn’t really care one way or another. I thought it was just normal and went along with my life, not bothering with this debate. But then I started hearing more and more personal accounts and then really just thought about them and turned them over in my mind.

Commentary

The first thing I thought about after seeing Winship’s illustration and the comments on it was, wow … what happened to art literacy and the shared communion of art? You could almost hear the walls of defensiveness slamming up by the minute as people bogged down in the limited framework of their individual and unique experiences with deafness, lashed out in knee-jerk reactions, and made assumptions about Winship without ever meeting or talking with the artist himself. I didn’t get the sense that many people took at least a few moments to reflect and ask whether the picture might be more a deeply personal expression and less a direct condemnation of them as individuals. I didn’t get the sense that they took his labor to heart and wondered … why? Why this? What drove this man to create this? What does the creation of this particular image say about us on a deeper level as a community and as a society?

Instead, many comments indicated that people viewed the image through their own individual frames of reference, took it literally, made assumptions about the artist’s intent, and interpreted it as confirmation of their own views. It resonated with some deaf people who oppose CIs as unnatural and argue for a child’s ability to choose what is done to their bodies, particularly when it’s not an immediately lifesaving procedure. On the other hand, for many deaf people with implants and parents of children with CIs who commented, it solidified their own generalized stereotype that the Deaf community is completely misinformed about and hateful of CIs and people who use them. It has been posted on thedeafcommunity.org‘s Bully File page as an example of anti-oralism, anti-CI bullying (the page, however, includes no examples from the other extreme despite many examples across the Internet).

All this furor raises the question … what is art? What is the value of art? What is the value of the reactions that art produces? Some quotes related to these questions that are very insightful:

No great artist ever sees things as they really are. If he did, he would cease to be an artist.

– Oscar Wilde

Art is the desire of a man to express himself, to record the reactions of his personality to the world he lives in.

– Amy Lowell

When I make art, I think about its ability to connect with others, to bring them into the process.

– Jim Hodges

Precisely because of all the reactions posted on the image and its iterations across the Internet, Winship’s art must NOT be censored, as some demanded, or even labeled as bullying, as the operators of thedeafcommunity.org have done. To do so is to oppress and attempt to intimidate and suppress one person’s truth. That hurts us and our society. Art like this should not be condemned and suppressed, but respected and accepted for the lessons we learn from the ripples it makes. I’ve written against censorship and suppression before – “Why Dirty Signs Should Not Be Banned” – and much of what I wrote then applies here as well.

If art is to nourish the roots of our culture, society must set the artist free to follow his vision wherever it takes him.

– John F. Kennedy

The piece has been labeled and devalued as propaganda, which it is not. Most definitions of propaganda require intent to persuade or manipulate. A site that explores art and propaganda says, “One form of expression lacks the intent to manipulate the viewer (art is the work that is play) and instead is made out of a need to release a sort of creative expression; the other form of art is created with the intention to manipulate the mass audience – propaganda art.” This is why it was so crucial for me to talk to Winship, to discover his intent and the inner source of and motivation behind his art.

Winship took all the personal accounts he had heard from former and current CI users, the discussions he had participated in, and his own musings, and he created in his art a reflection of one small slice of the outcome of that mishmash in his mind. He created a symbolic representation of his own perspectives and feelings. It is the personal expression by an individual, powerfully and technically very well drawn but which presents

One example of an ugly comment.

us with a disturbing image. However, it has elicited equally as disturbing reactions from both extremes of the spectrum. It has exposed to us the degree of ignorance,

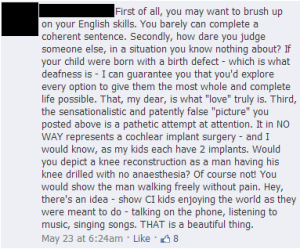

Another example of ugliness, from the other end of the spectrum.

misunderstanding, miseducation, anger and even fear that revolves around the issue of cochlear implants, Deaf culture and ASL, and what it is to be deaf or to parent a deaf child. Each and every one of those comments is just as much a part of the artistic experience as Winship’s illustration itself and has as much to teach us as the piece itself.

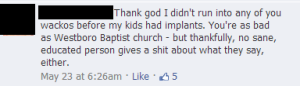

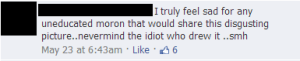

More ugliness.

They also force us to ask the question: Which is uglier and more disturbing, the image or the reactions to it?

Art “makes us attentive to the reality of our own life … Picasso and Cezanne help us understand that things can be looked at from several points of view at the same time,” Milton Glaser writes. This is the value of Winship’s drawing. What is not exposed cannot be corrected or confronted. Suppression prevents education, perpetuates closed-minded extremism and insensitivity to others, and aids concealment of those who are deeply entrenched in their prejudices.

The hope comes in this: Even as it has exposed ugliness, the drawing has spurred quite a few people to reflect and share their own experiences in an effort to inform and correct misinformation and assumptions and attempt to pry open the doors of people’s minds. It has brought out the beauty of the diversity of the deaf community and provided evidence that extremists cannot define the community, even as they seek to outshout and marginalize each other and ignore the bulk of those who sit in no-man’s-land.

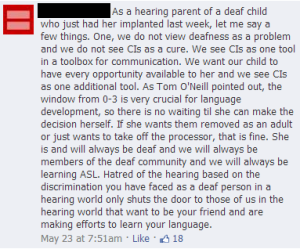

“She is and will always be deaf and we will always be members of the deaf community and we will always be learning ASL.”

Parents of children with CIs have come out of the woodwork to plead for rational, respectful discourse and share their efforts to expose their deaf children to the best of both worlds (despite backlash from both extremes). Deaf parents of deaf children have talked about why they chose to implant their children. Deaf adults with implants have come out to explain what their lives have been like, or why they chose to get a CI as an adult. And deaf people who grew up oral have come out to share their perspectives – not necessarily about CIs, but about what it is like to grow up shielded or restricted from contact with ASL and the deaf community. Deaf people who grew up signing or learned it later have come out to share their deepest emotions about identity and the culture so precious to them – and which they perceive some hearing people would prefer to obliterate much as eugenicists and Nazis murdered people with disabilities in the first half of the 20th century. That fear is real and deserves to be recognized and heard with the heart.

The frustrating part of reading some of these comments, for me, was observing two people on either extreme with the same core belief that they interpreted in diametrically opposite ways. For example, a deaf woman who views implants as unnatural and interference with God’s will that a child be deaf, while a hearing parent talked about implants as a miracle given them by God to help her child overcome a terrible impediment. If their roles were reversed, with their solid belief in God, would their views also reverse? The sooner we understand the common elements we share, the sooner we can achieve understanding. The sooner we recognize that we all look at the same picture very differently, for very different reasons, the sooner, perhaps, we are willing to listen.

People are naturally exposed to different slices of life and different types of people based on where they happen to be in life and who they interact with, and they will hear more stories of a particular slant than others. That’s why it’s so important to talk to and really listen undismissively to those unlike yourself, who interact with groups you don’t and live lives you don’t, so you can see a bigger picture than you would if you stayed within your own sphere of being. All of those perspectives shared by people – whether moderate or extremist – are emotionally and experientially laden and therefore valuable. They should be heard with open minds and hearts and a goal of understanding, rather than condemnation of the art or each other. This means that deaf people should be willing to listen to hearing parents who agonize over their children’s futures, and hearing parents should have the courage to listen to those who most intimately understand what it is to grow up deaf. But this listening did not happen with Winship’s illustration. People even more firmly shut the doors to their minds and hearts. What does that say about all of us?

Winship’s illustration accomplished one job of art: It got people talking. The other component of Winship’s art – the contributions by commenters – has another job to do: to get people to listen.

To conclude:

The aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance.

Republished with the kind permission of Tara at Jayhawkeditor.com. View the original article here. You can also follow Tara on Twitter.

The Limping Chicken’s supporters provide: sign language interpreting and communications support (Deaf Umbrella), online BSL video interpreting (SignVideo), captioning and speech-to-text services (121 Captions), online BSL tuition (Signworld), theatre captioning (STAGETEXT), Remote Captioning (Bee Communications), visual theatre with BSL (Krazy Kat) , healthcare support for Deaf people (SignHealth), theatre from a Deaf perspective (Deafinitely Theatre ), specialist lipspeaking support (Lipspeaker UK), Deaf Build Expo (SDHH), language and learning (Sign Solutions), sign language and Red Dot online video interpreting (Action Deafness Communications) education for Deaf children (Hamilton Lodge School in Brighton), legal advice for Deaf people (RAD Deaf Law Centre).

Callum Fox

June 14, 2013

Superbly written piece and I applaud Tara for a really interesting interview. Plenty of food for thought.

John David Walker

June 14, 2013

Can I congratulate Limping Chicken for publishing such an informed article. I think we are often too quick to express our opinions here and not give ourselves time to reflect and find support to our thinking. Writing in the heat of the moment does not always create the most informed piece of work.

I only wish LC did the same with the Rita Simons situation as it would have benefitted equally from an investigative and reflective essay on the potential relationship between CIs and abuse.

Editor

June 14, 2013

Thanks for your feedback John! Glad you found this great interview informative. Ed

Hartmut Teuber

June 15, 2013

I am not on the Facebook. So I cannot comment on Winship’s creation.

All the reactions that is quoted and commented about in this blog are just emotional reactions to the picture, not critiques to the art and symbolic message behind the picture.

The picture’s significance, although I haven’t seen it, may rest upon what deafness is to mean for life, humanity, and society. That is where the critique of the picture is to lay.

The critics appear to have failed to accept that the inability to hear is not a defect in a human being, but is simply a variety of mankind, which provides challenges to the mutual coexistence between hearing and non-hearing human beings. The furor from Winship’s picture has revealed exactly this problematic tension between the two groups..

Carrie M

January 21, 2014

You awe the biggest jerk and asshole for hurting people feelings.. Yes we are still deaf without our implant and I don’t use big D because I have both world… Small d and hearing world… You can’t just tell people nit to get implant and really not your choice…. I love my Ci’s implant and damn proud to hear … You need to grow up and shut up!!!!! No one like you!!!!!!!

Yolanda

May 27, 2014

Can we please do this in a polite way? I have a CI, and my parents made the decision to implant me when I was young. I thought this article was really interesting and two sides of this debate. I rather tell my opinions to my debaters in a polite way, because it will receive respected attention. Remember, there is no right answer to this debate, and will likely to continue to be this way till something changes.